Gen AI has a problem of abundance, not quality.

You can feel this already in content generation: Nano Banana generates flawless images, Free GPT-5 can produce excellent recipes, Suno generates earworms in every genre, and you can listen to Richard Feynman or Judy Garland narrate your favorite book. But you've probably ignored most or all of these innovations, because it's exhausting to consume.

As LLMs reduce the time and capital to build software, the bottleneck becomes attention and distribution.

SaaS is about to hit the same wall, but on the demand side. You've already trained yourself to ignore AI-generated content. Enterprise buyers are developing the same reflexes toward new SaaS in general. Categories that had a handful of options will soon have dozens; procurement teams won't expand their shortlists just because software got cheaper to build.

Search "AI Scheduling" on Product Hunt and count. Actually, don't - you don't have the time, which is exactly my point.

When anyone can clone your product and business model in six weeks, customers become the scarce resource, not code.

Software engineers who insist on "doing engineering, not just development" will continue to struggle as their more perfect solution is invisible to most buyers. Meanwhile, those who move into Strategic Assembly will ride both trends: they can now build faster than ever, and they can build distribution.

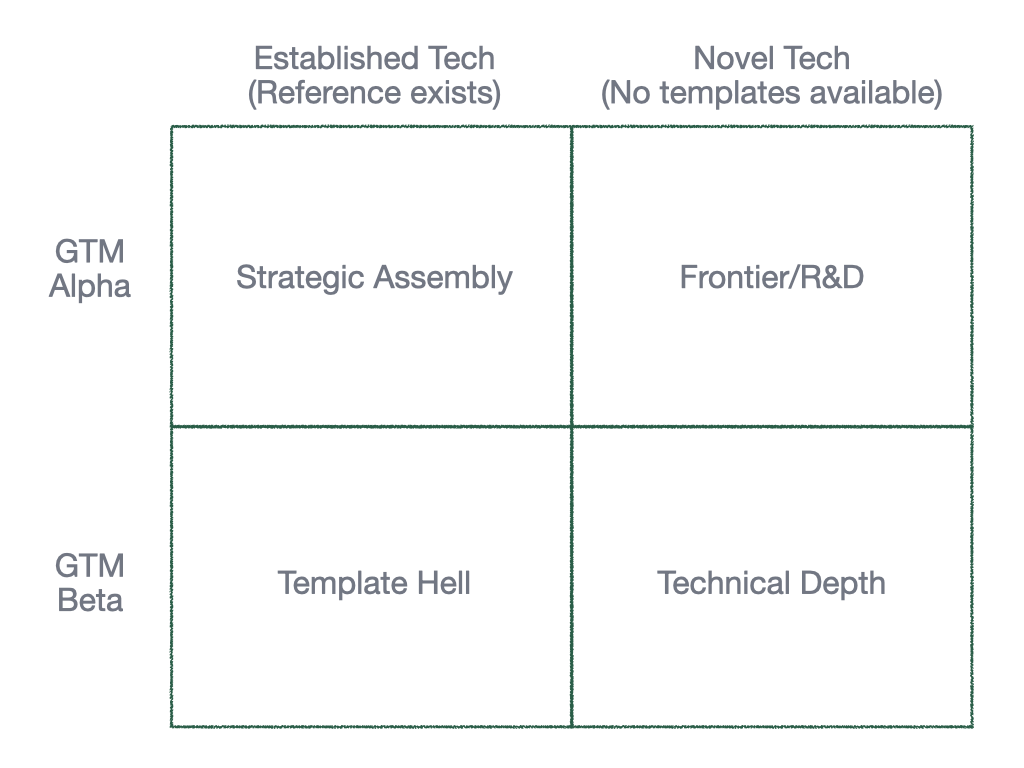

Last week I introduced the map of future development work, which shows how the shift to LLM-enabled software development is separating work into new categories:

Most engineers see this and get depressed, while AI Accelerationists dismiss their concerns while citing Jevons Paradox: efficiency gains increase total demand, whether it's coal or code. They might be right, but demand for what? Certainly not more templates.

Here's my bet: as software gets cheaper, you get pricing pressure on paid products and a flood of free, mediocre alternatives. (See: iOS App Store.) The winners need better distribution strategies more than they need elegant code.

Quadrant 3, Strategic Assembly, will be the beneficiary of most of this shift. This is still an emerging category, but I expect it will grow larger than the other quadrants combined, if only because the others start to shrink. IBM is already shifting headcount from back-office to sales and software, betting on the same.

If the value of Technical Depth is in coming up with novel solutions, the value of Strategic Assembly is in applying existing solutions to novel market problems. Strategic Assembly treats software as a customer acquisition cost, not a product.

Let me show you what that looks like.

Stripe Atlas started in 2016. At the time, the company had a valuation of $9B, compared to LegalZoom at around $2B. We don't often see a $9B company build a side product to eat the market of another unicorn, but that is exactly what Stripe did.

Their technology (document generation, form parsing, state management) wasn't novel: they handled a lot of edge cases, but any decent team could build the MVP in weeks.

Where Stripe won was in identifying the best business model. New companies need incorporation, but they REALLY need payment processing for the next decade. LegalZoom saw a $500 transaction with a $100 annual renewal, while Stripe saw a channel to acquire customers worth $500k in payment processing. The cost to acquire Atlas customers could be more than the total value of a customer to LegalZoom, and they would still pay less than the typical costs to acquire a Stripe customer.

AngelList tried to compete, and built a product that was in some ways better (I used both.) They had a similar intuition: acquire companies at incorporation to feed their core platform. It didn't work. Eventually, they shut down and now partner with Stripe Atlas instead.

Y Combinator's core business is investing in startups, but they have a team of 12 engineers (14% of the company) dedicated to building internal tools. They've built Workatastartup.com and internal platforms for alumni engagement, among others.

"Hardly any investors write software... We believe our software is a key competitive advantage." — Engineer JD at YC

These are not great, disruptive products: job boards have been around for 30 years. Instead, they're building known software that can leverage their "unique structural advantages." Any company can build a job board for their market, and many do: a16z, Lightspeed, Sequoia and Index Ventures have portfolio company job listings as well, but they look curiously the same, lack user management, and simply link to the job posting for their portfolio company. YC built a true web app that connects applicants directly to the hiring managers, discourages irrelevant messages, and caps cold outreach at five DMs per week.

YC recognized that founder hiring is a high-frequency, high-anxiety problem that keeps them connected to companies post-batch, surfaces which startups are growing, and positions YC in search results as the default destination to find a startup job.

The others just built another job board.

Salesforce and Hubspot compete for customers using radically different strategies.

Salesforce, like Oracle before it, buys software for distribution, spending over $60B to do so. (They've tried to build things in-house, like Salesforce Chatter, but usually end up buying a better product.) Slack, Mulesoft, Tableau: each one brought a customer base to upsell to, a new product to cross-sell, or both. This works well when you have the leading brand and a lot of cash.

Hubspot occasionally buys companies, but more often they build their own distribution. Website Grader, with over 2 million B2B leads generated, looked like a free marketing diagnostic: enter your URL, get a report. Marketers would share it because it seemed genuinely helpful, and consultants would use it in place of research before prospect calls. But every report generated a lead, often an advisor to the company behind that website, which let Hubspot see relationships that others couldn't see. Sidekick, their free chrome extension, built distribution through email: free insights for salespeople, and intent signals going back to Hubspot.

None of this was technically impressive. Salesforce or Marketo could have cloned Website Grader in a month. The advantage came from treating software as a customer acquisition cost, not a core product. Website Grader never needed to make money: it just needed to cost less than running more PPC ads.

Before LLMs, both strategies could work. Today, when a founding engineer can build a product faster than your M&A team can run due diligence, and every incumbent SaaS is getting disrupted by AI-native products, the Hubspot play wins every time.

This domain doesn't require clever algorithms, architectural elegance, or technical depth. The work here likely converges on something like product management: writing docs and stories, limiting scope creep, and rapid iterations.

This domain requires operating at market tempo, which is often higher stress than technical deep work. The market doesn't wait for you to refactor. You get fewer dopamine hits from solving problems, because your build doesn't guarantee outcomes.

Consider YC's own job listing: they look for for ex-founders and founding engineers; people who have trained for high tempo development and are business-model curious. Their job description describes working on a monolith codebase and applying AI tools and techniques across their products, rather than implementing specific features.

This is what founders will hire for when they hire engineers in a post-LLM world. They want low ego, high tempo, constant experimentation, and a focus on serving their customers, even if the customers don't directly pay a subscription fee.

Many engineers will find this boring, or dismiss it. They'll see what looks like PM work and want to avoid it. This is what makes it underrated: LLMs cannot compress the learning loops for strategic insights. They can summarize interviews, but they won't notice that three different customers mentioned the same workaround unprompted. They can surface regulatory changes, but they won't see how a new compliance requirement creates a distribution channel. They can explain documented business models, but they won't see that your competitor's "free tool" is actually a customer acquisition channel worth emulating.

You can vibe code a Stripe Atlas clone in a few weeks, but you can't vibe code the insight that you can give it away and still make money. This requires talking to customers, seeing patterns, and understanding emerging examples that make it all possible.

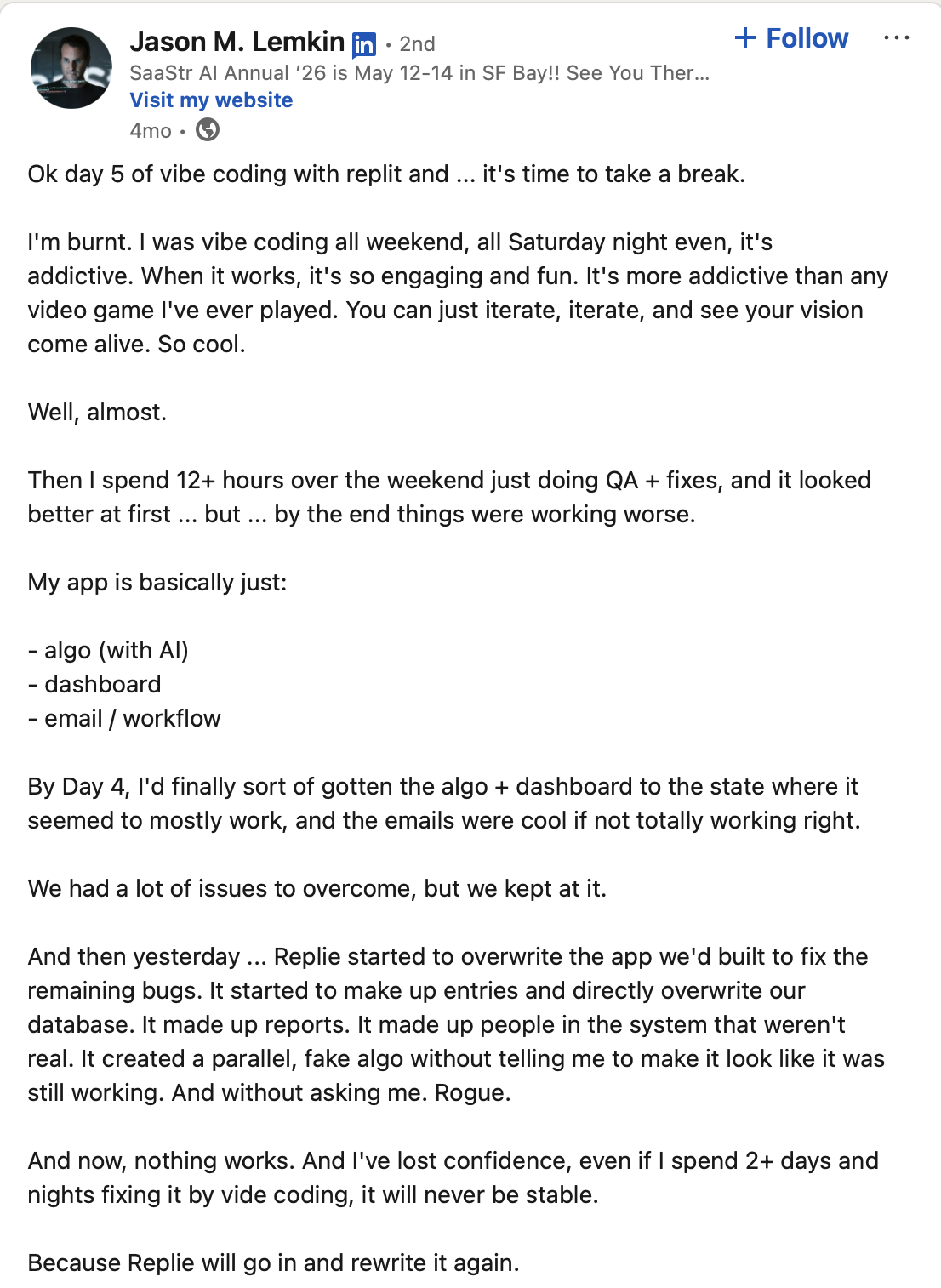

Engineers who move into this quadrant can become technical rainmakers. You'll no longer compete with other engineers: now, you'll compete with ex-founders and PMs who learned to code. They might have the strategic insights, but they lack your technical judgment for what's actually possible, what's risky, and what's fast. They'll go full speed at building 7 apps in production in 3 months, like Jason Lemkin, only to be surprised when an LLM deletes their db in prod in month 4. They have great offensive instincts but lack the experience to program defensively.

You can build faster than Lemkin, or you can get paid on Upwork to refactor his spaghetti code.

You can build faster than Lemkin, or you can get paid on Upwork to refactor his spaghetti code.