A Senior iOS frontend developer I know worked as a founding engineer early in his career, but spent the past decade working as "the" iOS guy at every employer. He recently told me his designers started using AI to generate prototypes. "It's great", he said, "makes my job easier. I don't have to build as many early versions or argue as much about what we can do."

He doesn't realize what just happened.

The designers don't need him for rough drafts anymore. His role was just significantly reduced by LLMs. Before, he was the expert builder who translates images and mocks into Swift. Now, it is just "polish the designer's prototypes and fix bugs." He thinks AI makes his job easier, and it does. When the designer can handle the early iterations themselves, what's left may not justify a full time role. His job is becoming so "easy" that soon he won't have one.

This is the conversation we're not having: which software engineering work is AI eating next, and where will we have defensible value?

I meet with a dozen engineers each week in HCMC, Vietnam: mostly expat indie devs building side projects. Yesterday, everyone was comparing their tools. One guy said something that surprised me:

"I don't use AI much. I know it works, but I don't enjoy it. When Claude writes code, I have to then review it, and I hate reviewing code. I got into this because I like writing code. I love that dopamine hit when I solve a problem."

Another senior engineer jumped in: "I agree. I get tired reading LLM code all day."

Here is what they are actually saying:

"I chose engineering to be a highly paid builder, not a manager."

And AI just turned them into managers anyway.

Think about what vibe coding actually requires:

These are management skills. Specifically, these are the exact skills you need to manage offshore or junior developers.

I've spent a decade managing offshore staff and interns. I'm not a great engineer, I probably can't even whiteboard a sorting algorithm. But I can now ship production-ready code with LLMs, because the bottleneck shifted from "can you implement this?" to "can you specify and review this?" When I started vibe coding, the tempo surprised me, until I realized my approach is different: I treat LLMs like savant junior devs who need structure.

Effective use of AI looks like engineering management at 10x speed. Engineers willing to embrace this can ship like a small team while working alone.

Most engineers don't want to be Engineering Managers. They specifically chose the Individual Contributor (IC) track to avoid management. No future advancement in AI is going to make them happy again; every improvement in frontier models eats further into their solo dev work.

For the last 20 years, being a great IC has paid so well, that you didn't need to do anything else. If you love solving puzzles, taking your time to get things right, and making money from your sheer competence, you were probably well compensated. That era is ending. There will continue to be niches where engineers make great salaries while acting as a wrapper around an LLM, but your paycheck now depends on the ignorance of the person signing it.

So where does that leave engineers who don't want to manage? It depends on what kind of work they're doing.

A quick detour on terminology: GTM (Go-to-Market) refers to how you acquire and retain customers: your distribution, positioning, and competitive strategy. This is often reduced to "scale cold email" and most people with a GTM title are salespeople, but companies are increasingly hiring "GTM Engineers" who sit in marketing and take a broader view of the market beyond "send more email."

Alpha and Beta come from finance: alpha means the excess returns that disappear once everyone discovers them, while beta describes the market returns from following the standard playbook, like an index fund.

Before LLMs, implementation was the engineering skill. Every problem required Technical Depth: even choosing a library that wouldn't bite you later could take a full day of reviewing each repo, trying out implementations, and getting a feel for whether you wanted this dependency. Today, that fits within one chat session.

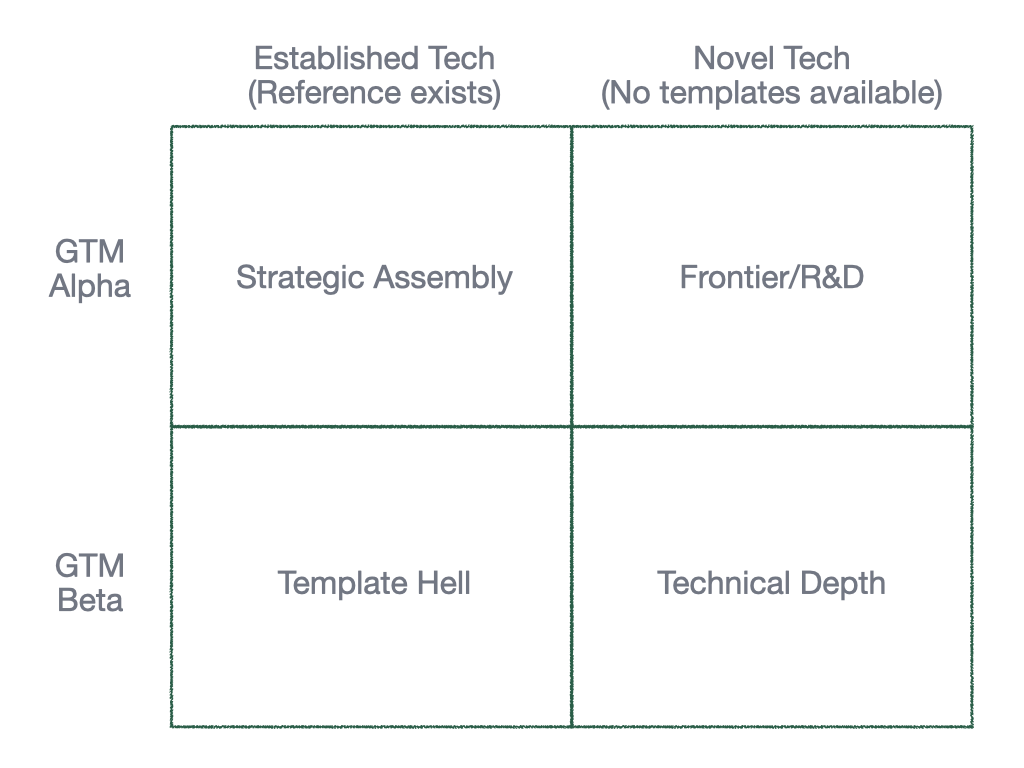

With LLMs, there are now four types of Software Engineering work, defined by two dimensions: whether the tech is solved or novel, and whether your competitive approach is Alpha or Beta.

Most engineers focus only on the tech dimension and assume the business side will handle competitive strategy. With LLMs, this separation no longer works. When implementation becomes cheap, the defensible skill shifts from building to knowing what to build and why it creates competitive advantage.

Let me show you what these look like in practice.

When a problem is well established, and the solution is well established, you are in template hell. Here, LLMs work nearly perfectly, and senior engineers feel worthless.

A year ago, I had an idea for a chrome extension. Total time to develop was less than an hour, and that included 20 minutes arguing with an LLM over whether a 2,000 year old text was copyrighted.

Naturally, I started to feel like a genius. I have some coding experience, but had never built anything faster than it took to write a blog post.

That all changed a month ago.

A friend who has worked in telesales for 30 years shared an idea for a sales tool. She'd been thinking about this concept for months but had never built it: she's not an engineer, she doesn't know how to code and doesn't have the time to learn.

I built a prototype in a day using basic pieces: Cloudflare, Clay, Claude, and Webhooks. Just straightforward data enrichment piped into an email template: something a buyer like this would pay two weeks of labor for in 2022.

She saw my demo. Two days later, she had built the same thing herself. Zero coding background. Pure vibe coding.

I thought I was demonstrating value by building the prototype. Two years ago, that would have moved us toward a contract. But now, I was just demonstrating that the magic had disappeared. I broke the 4 Minute Mile for her. This project which had intimidated her technically had turned into Template Hell work: established problem, established solution, and plenty of reference implementations. All she really needed was my screenshot and the courage to try.

If someone with zero coding experience can build your two week prototype in two days after seeing one example, you're getting replaced.

Her demo might not be production-ready code, and it probably has security flaws, but it doesn't matter, not yet. She has a home-cooked app that meets her needs, without working directly with another human.

The people rapidly adapting in Template Hell are not the best coders. They are:

Notice what's missing? "Great IC engineer with no management experience."

The good news: you can learn to manage LLMs without mastering people skills. The next decade will be a golden age for introverted managers. But you have to learn. And even then, Template Hell might not be where you want to play.

"(My new project is) basically entirely hand-written (with tab autocomplete). I tried to use claude/codex agents a few times but they just didn't work well enough at all and net unhelpful, possibly the repo is too far off the data distribution."

— Karpathy

The Technical Depth quadrant is where LLMs can't one-shot your solution, because they've never seen that solution before. LLMs hit walls where they haven't seen reference implementations.

Most serious engineers will gravitate to this quadrant. They want to learn new things, while keeping to problems that are well understood. They want to feel like the first to find the solutions. They love the idea that there are still illegible parts of the latent space where they can discover something before an LLM.

Maybe you'll rebuild a distributed cache in Rust because "performance matters." Or you'll hand-optimize an algorithm because "efficiency is craft." Here, the LLMs can't quite pattern match, the solutions haven't been published in a public repo, and you probably can't even use GoogleFu.

If a founding member of OpenAI hits a wall with vibe coding, then the wall is real.

But notice what Karpathy is writing by hand: a reimplementation of core ML infrastructure, for fun, of systems he helped invent. This is technical depth as hobby. Karpathy can afford indulgent work because he's already worth millions. Most engineers can't, but they chase the same feeling anyway.

This is the dopamine trap. It's not new: in 2016 it looked like a dev rolling their own Parse implementation to avoid paying $10/mo. Then, you could almost justify it: you learn something new, you avoid vendor lock-in, you make exactly what you want. The gap between "do it yourself" and "use a tool" was maybe 3x.

Today, that gap is 50x or 100x. Novel to you does not mean it's novel to LLMs.

Many devs will try to use an LLM on the problem once, get garbage output, and conclude they're too far off the data distribution, when they are actually in Template Hell and don't know it.

There will be real work in this quadrant for a long time. But every other engineer fleeing Template Hell will default to competing here. Supply will outpace demand. This pressure will increase the supply of published solutions; every published, documented solution becomes training data for the next generation of models, until today's Technical Depth becomes tomorrow's Template Hell.

This is the real R&D area: foundational model research, quantum computing, major bets that take 5+ years to reach the market.

This is your quadrant if you want to do Important Work™, but in software, this quadrant may shrink: frontier AI companies continue a trend where capital and compute grow faster than labor. Meanwhile, organizations can only absorb so many paradigm shifts per decade, regardless of how fast researchers produce them. The bottleneck is not discovery; perhaps it never was.

Those working in this quadrant often fail to capture the value of what they create - at least not as employees. Noam Shazeer and his co-authors on "Attention Is All You Need" watched OpenAI capture the early value from their research. They had to leave Google, start their own companies, and commercialize their technology. If you want frontier work and financial outcomes, you'll probably need to become a founder too.

The biggest trap engineers will make is to work on trivial problems while imagining they are working in the technical depth or the frontier. A lot of work can actually appear to be trivial until its value is discovered, so this is a particularly difficult trap.

Sometimes it will be obvious: bike shedding will always look like bike shedding.

Other times it will be less clear. If you work in regulated industries (healthcare, finance, aerospace) you may assume domain complexity will protect you. It doesn't. Your only protections come from implicit domain knowledge. If you're implementing specs someone else wrote, compliance requirements don't change which quadrant you're in.

Engineers maintaining legacy systems fall into a similar trap: assuming tribal knowledge is a moat. This moat is rapidly eroding: every increase in context windows, every internal doc you write, every system you explain to a new hire erodes it. At some point, your company will discover it's cheaper to rebuild with LLMs than to maintain with humans.

Here are some questions you can ask yourself to figure out if your work will still matter in a few years:

If you answered honestly, you probably just realized you're in Template Hell, or competing for a crowded spot in Technical Depth.

Most engineers are.

But there is a quadrant we haven't covered.

Where the value of Technical Depth is in coming up with novel solutions, the value of Strategic Assembly is in applying existing solutions to novel market problems: specifically in distribution, customer acquisition, and competitive positioning. When building is cheap, advantage shifts to market insights.

This often looks like side projects that become their own business, or new integrations that give you access to customers. Think of it as using software to solve distribution problems rather than product problems. Stripe, Y Combinator, and HubSpot all innovated in this space before LLMs.

Remember the iOS developer in the beginning? He's built some good apps on the side to serve specific niche communities. He already knows how to identify underserved markets, he just never saw distribution as his job.

Next week, I'll show you how Stripe used a side project to eat a unicorn.